The Basics of Research Cruise Planning

- Rosalie K. Cruikshank

- Jan 5, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 24, 2025

Over the past few years of my undergraduate degree, I have been involved in planning and participating in a few different research cruises: for long-line fishing and collecting sediment cores for Deepwater Horizon oil spill research through the Scientist at Sea (SAS) program at Eckerd College, for collecting a sediment trap and water samples for my job at the United States Geological Survey (USGS), and for analyzing shipwreck sites with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) for the Peerside Program through the State of Florida Institute of Oceanography (FIO) (Fig.1). There are many different factors to consider when planning a research cruise such as cost, time at sea, data collection and analysis, and equipment. Therefore, planning far in advance is of the utmost importance.

How do I start to plan?

If you are anything like me, when you first heard of a research cruise you may have had no idea what that involves or where to start. You may have wanted to dive right into the nitty gritty and try to accomplish things as fast as possible. However, to understand how to start you have to understand why you are planning and what you want to accomplish. This can be the most challenging part, because you may know what types of analysis you will be doing, or what you want the end result to be. However, it is important to know how to get there, how to develop a research question and objectives, and how to figure out what you want to learn along the way.

A good way to orient yourself is to start writing things down:

Lay out what you know already, and what you want to figure out.

Find research that has been done in the area in the past and read up on what questions they answered and how they got there.

Start writing down potential objectives based on the types of data collection and analysis are available to you.

Compile any information that you think may be helpful.

Doing these things should help you evaluate what is possible and what is not within your limits. Finding an advisor who is experienced in your field will be invaluable to your progress along the way. They can help answer questions and guide your research in a direction that will be accomplishable. However, be careful not to lean on an advisor too much; it is important to figure some things out on your own so you know the purpose for doing them. It will be difficult at first, but you will learn so much along the way, be grateful for the experience, and walk away with skills that will serve you well in future research or a career.

Planning the Details

Once you have your research question and objectives, the next step is figuring out what you need to do to accomplish them. Again, an advisor will help you through these steps, but it is important to be involved in the process so that you know the plan and how to follow through while you are at sea. There are several elements that will need to be planned out, such as:

How many days will you be at sea?

What course will the vessel take (considering time and cost efficiency) to be able to collect all necessary data?

What equipment will need to be used?

How to prepare the equipment in advance

What the samples will be put in

How to label the samples

What analysis needs to be done at sea, and what can wait until land?

How will you coordinate with the ship's technician/engineers/captain?

What needs to be packed (for the research and for yourself)?

What needs to happen once you make it back to land?

Depending on the type of research cruise, these steps will vary. If you are thinking, "This is way too much! I don't know how," do not worry - that is normal, especially if it's your first time. Again, a good place to start is to research similar things which have been done previously, such as sample collection and analysis methods, labeling schemes, and packing. Ask lots of questions along the way to learn all that you can! If you are unsure of anything, it is best to ask sooner than later. You do not want to be stuck in a situation where you are expected to know something and regret not asking more questions while learning the process.

When planning the research cruise for the SAS program, we knew which sites we needed to get to for collecting samples, but had to plan the route. We had to account for a slightly slower ship speed than planned and the amount of time sample collection would take at each site in order to fit everything into the time frame at sea (Fig. 2).

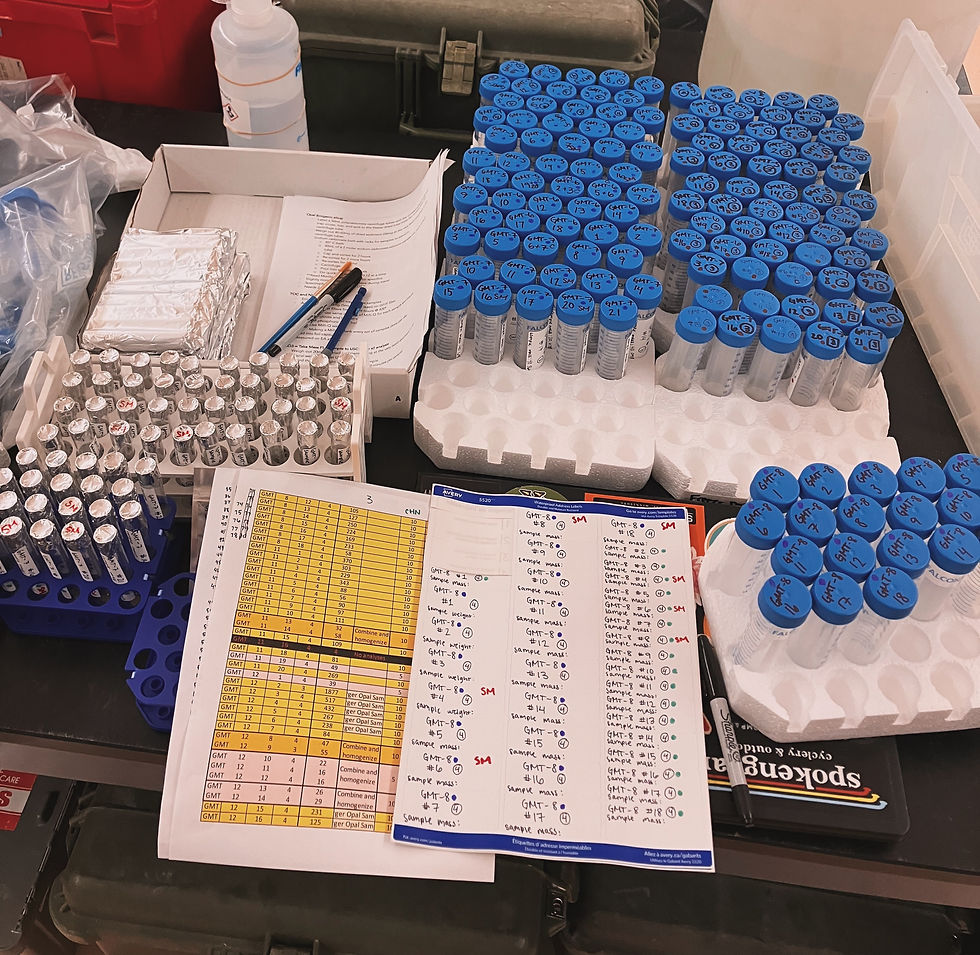

An example that I have for preparing sample labeling schemes is for my work at USGS. Each cruise project has a name abbreviation and then cruise number associated with it that goes at the beginning of the name. Next is the cup number from the sediment trap, and then the portion of the sample after it has been split into four different samples. The final product is something like "GMT-1-12-4" (Fig. 3). This name stays with the sample from the time it is collected, to the final composition processing. Keeping the same name throughout the process keeps things consistent and leaves less room for confusion.

To figure out how to collect samples, you must use the equipment available. On the SAS cruise, we were aboard the Research Vessel (R/V) Weatherbird II, which has the capabilities to deploy something called a multicore (a tool used to collect several identical sediment cores from the seafloor at once). This is how we planned to collect all of our sediment samples. However, when planning the Peerside cruise, we wanted to use the capabilities of the ROV. Instead of using a multicore to collect the sediment samples, we planned to use the ROV to collect push cores from the seafloor.

The last example I will give is for deciding what to do at sea and what to wait for until you get to land. Some of the water sampling which I did with the USGS was time sensitive, because we did not want to incorporate more oxygen into the water or let nutrient counts vary from what was present at the time of sampling (Fig. 4). In contrast, sedimentology for the SAS program did not need to be done immediately after sampling, so we waited to extrude the sediment cores into smaller subsamples until we were back in the lab on campus at Eckerd College (Fig. 5).

Executing the Plan

Once a plan has been made, everything is prepared, and you are all packed up, it is time to go to sea! Do not be too nervous, this is an exciting time where you will get to be a part of important research and learn so much. Take things one step at a time. My first time on a research vessel I remember feeling a mix of nerves, excitement, and imposter syndrome. I could not fathom how I had been given such an amazing opportunity and the responsibility and trust to do real research with real scientists. But, by remembering all of the preparation and learning I had done to get to that point I realized that everything would be ok and that I knew what I was doing.

It is a saying among some research groups that there will always be something that goes wrong on cruise. I've known professors who have lost important sampling equipment, and have personally experienced cruises getting cancelled and preparing for a hurricane while in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. When something goes wrong, you just have to figure out how to roll with the punches. It may feel scary or even devastating to your research and experience, but things will go on and you will find a way to make it work. It may even lead to in a new and better direction than before. Be prepared for a change of plans, and do not be afraid when you must implement them.

What Happens After?

It is a big accomplishment to get through your first research cruise, but what do you do after it is over? Chances are, you will have to do some more sample processing when you get back to the lab you work out of. Then, data will need to be analyzed and eventually written up so that other scientists can learn from what you have discovered. Keep your eye out for my future blog posts where I dive deeper into what sample processing and writing entail, and how to get started on these tasks which can seem daunting before you begin.

Comments